This and the upcoming issues of the TSU Rector’s blog are devoted to the concerns related to the end of the “Bologna” era of the Russian higher education and the transition to a new stage of its development.

— Professor Galazhinskiy, how did you take the news from Deputy Minister of Science and Higher Education Dmitry Afanasyev when he said, “It is the Bologna system that withdrew from us, and not we from it”?

— I took it well, as did all my colleagues, rectors of Russian universities, who signed the appeal of the Union of Rectors to support the President of the Russian Federation on the special military operation. This was something we expected, considering the growing cultural and civilizational divide between Russia and the West, as well as countless Western sanctions against our country. Formally, the Bologna group was ahead of us in deciding to go their own way, but, in fact, we were already prepared for this departure and now we are crossing the Rubicon.

— Don't you think that "one’s own way" has long become a kind of Russian meme that irritates all domestic neoliberals, not to mention our "frenemies" who live in the West?

— Maybe. And this is quite understandable. In our time, when national sovereignties, identities, and basic human values are being eroded literally before our eyes, not everyone can afford to go their own way in politics, economics, culture, science, and education. For most countries, this is an unreachable dream that causes envy and irritation. For us, this is a conscious choice dictated not only by today's circumstances, but also by responsibility to the future generations of Russians. Obviously, “one's own way” will be one of the most difficult and longest, but, as they say, the journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.

— Some researchers believe that even being part of the Bologna process, the Russian higher education differed from the European one. Would you agree with it?

— It couldn't be otherwise. Despite the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the traditions of the Soviet higher education turned out to be so strong that they could not but be reflected in the mirror of the Bologna system. However, under the new conditions, this was not a matter of pride for our country. For having "our own way" we were criticized not only by experts from abroad, but also by domestic ones. I remember a scientific paper on the topic that even began with a quote from Viktor Chernomyrdin: "No matter what we do, we end up with the CPSU..." (the Communist Party of the Soviet Union). The paper stated that the bachelor's degree in Russia is not the same as the bachelor's degree in the West. It is our good old specialty, which was shrunk to four years. And all the other parameters of the Bologna system were "customized" for us as well.

— One way or another, we were part of the Bologna system for almost 20 years. It may not have become our “flesh and blood”, but we have already gotten used to this system and realized that, along with shortcomings and problems, it also had certain advantages. For example, the multi-level "bachelor's degree - master's degree" system, which suited some people better than a five-year specialist training program. And now will we need to start from scratch?

— The uniqueness of the moment is that we can and should keep all that is good for our domestic system of education, which we have already got used to and which can continue to work efficiently. This is exactly what Valery Falkov spoke about in his interview with the Kommersant newspaper in early June, as well as in a subsequent speech “What is the future of the higher education in Russia?” at the parliamentary hearings in the State Duma of the Russian Federation

The variability of the formats of education is an obvious advantage, which we should not ignore. Another thing is that there are educational areas for which there are priority formats of education. For example, for training in medicine, engineering, and various interdisciplinary areas the specialty training would be appropriate. There are new formats that have appeared that have already shown their effectiveness in university practice. For example, integrated master's programs with a six-year term of study. Viktor Sadovnichy, Rector of Moscow State University, spoke about it in details at the same parliamentary hearings. In any case, the Bologna Declaration, signed by Russia in 2003, does not oblige us to part with bachelor's and master's programs (or anything else) in case we leave the Bologna Group. The Group does not own the copyright for bachelor's and master's degrees as formats of training, and, accordingly, for bachelor's and master's degrees as academic qualifications. It came to the modern world literally from the depths of centuries and became a common property.

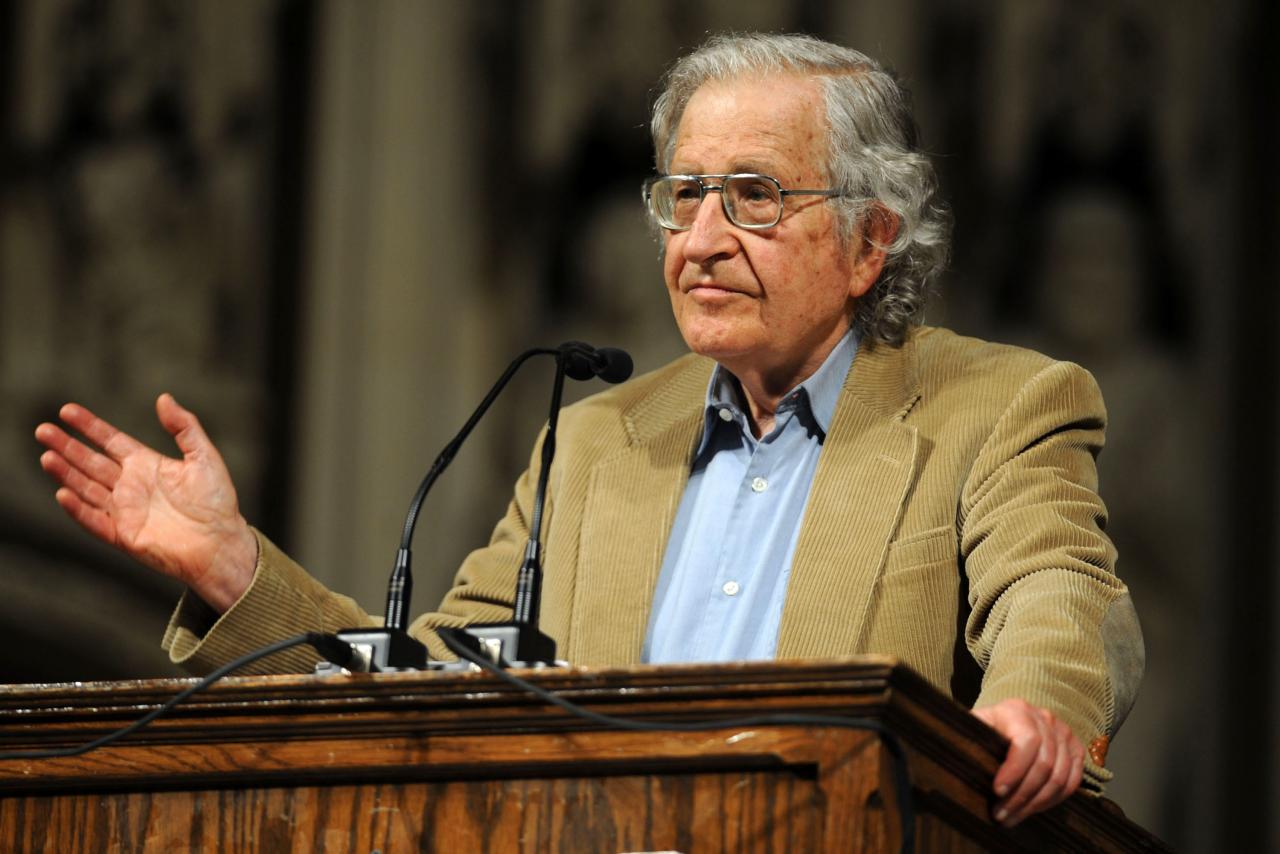

As for the breakdown, I would prefer to call it differently "another educational reform". Such reforms periodically occur in all countries, and especially at those moments when the political and economic course changes dramatically. It would be strange if it were otherwise. The connection between education, culture, politics, and economics was very well revealed by Noam Chomsky, an outstanding American researcher, philosopher and publicist, one of the most cited authors in the world after Plato and Freud. Many people know and remember his 2012 lecture “Education: For Whom and For What?”

In his speech, Professor Chomsky talked about the long existence of two points of view on the goals of education. According to the first one, a student is an empty vessel, and not a very hermetic one. Accordingly, education is the process of filling a leaking vessel with knowledge because it is quickly forgotten. By the way, at one time another American social philosopher, John Dewey, admitted that it is short-sighted and immoral to educate the children of workers not according to their will and without their understanding of the matter, but only for the sake of the experience. In this case, the vessel will always leak. According to the second point of view, education is a kind of “guiding thread”, along which each student takes their own path. This particular idea was taken by Wilhelm von Humboldt in the 19th century as the basis for the model of the modern classical university.

These two points of view can exist both in opposition to each other, if the issue of a single model of education “for all” is being decided within the framework of the concept of the welfare state. Or if we are talking about two models of education at once: for the absolute majority (regular citizens) and the intellectual minority (elite). According to Chomsky, the model of education as “filling an empty leaky vessel” with relevant knowledge and ideas is, in fact, an instrument of social control. It helps to bring up obedient voters. As for the “guiding thread” model, it prepares the “wealth of the nation” and is responsible for everything that happens in the state. And the whole history of world education, one way or another, revolves around these two models, primarily due to ideological reasons. We can say that this is the “law of the cycle of educational reforms” discovered by Noam Chomsky.

– Nevertheless, in the domestic public consciousness, each previous educational reform is not perceived as “natural” and corresponding to a certain historical stage, but as “erroneous”. This is probably where mistrust of every upcoming reform grows. It also seems that our education system is the only one continuously taking one step forward, two steps back, while the system of the West develops progressively.

– This is just an illusion created by the media and supported in the everyday discourse. The stereotype "apples from the neighbor's garden are always better" works in this case too. The history of the Western education — American and European — has recorded no fewer conflicts than the history of the Russian education. And maybe more. Chomsky speaks about it in his lecture too. Not everyone knows and remembers that, despite having its own universities, until the 1940s, the United States was a kind of cultural and intellectual province. Everyone who wanted to become researchers, writers, or artists had to go to the Old World: Germany, Great Britain, France, and Italy. We do not know how long this would have continued if not for the Second World War. The most brilliant brains and talents of the Western Europe, emigrated overseas, hiding from German Nazism. It would seem that the United States should have welcomed them with open arms and taken the opportunity to gain valuable knowledge and experience first hand. But that was not the case: by the mid-1940s, the Americans were overwhelmed by the “spirit of triumphalism” thinking they were victors in World War II.

Everything that came from conquered Europe was beneath them, including science. American education was dominated by the message: “Throw away all the old baggage of knowledge! Forget all the European nonsense and start over: Come to the brighter future of the American age!” According to Chomsky, Americans thought of European scientists as "old baggage." And this policy extended to all stages of education: primary, secondary, and higher. This ignorance had many consequences, and some of them are still observed today.

In their denial, the Americans then went so far as to even invent their own sciences and disciplines. So, for example, Chomsky was amused by the attempts of the teachers of his young children to teach them “new mathematics”, which did not have any serious theoretical basis whatsoever. At the same time, during those same years, positive changes took place in American education. A completely new contingent came to universities because of large benefits for the demobilized soldiers. Those were people who could not get there before. And this has had a very positive impact on colleges and society (by the way, this is not a current policy in the US). This contradictory situation in American education continued for quite a long time, until 1957, when the Soviet Union launched its first satellite. This was followed not only by a sharp increase in funding for science and education, initiated by the Pentagon, but also by a revision of the curricula for all levels of education.

At present, education in the United States, in terms of its goals and quality, is rather controversial. Chomsky's models are vividly represented in it as never before. On the one hand, there are American universities that do not leave the first lines of the world rankings. They prepare the elite to manage the American and world economy and politics. On the other hand, there are public schools and colleges that prepare future obedient voters and executors of the will of the elite. Nobody is really bothered with the quality of education. For example, in high schools students can choose from just one of three so-called sciences: biology, chemistry, or physics. It is clear that biology is more often chosen as a descriptive science. As a result, it is a civil feat for an ordinary American to turn off the electricity and fix an outlet at home.

Until now, as a rule, those who major in natural sciences, mathematics, and engineering at American universities are international students. These are "brains" capable of understanding theoretical physics and mathematics. It can be said that today US universities are more concerned not with the quality of education, but with issues of gender diversity, the BLM movement, and the like. It is no coincidence that former President Donald Trump, speaking recently to American students as part of his new election campaign, touched on precisely these topics.

— It turns out that the Western European-Bologna system is the embodiment of the dream of philosophers about the welfare state and a better world, as it focuses on mobility and individual educational trajectory for everyone, not just for the elite, as well as its special attention to the quality of education?

— I must admit that the initial ideas, from which the modern Bologna system gradually emerged, were very attractive and reasonable. First, it was the idea of a united Europe, which gave hope for preventing a new world war. The disasters of the past taught Europe that it cannot survive if it remains fragmented. They began to talk about this immediately after the end of World War II. It seemed that if the peoples of different European countries were "mixed", it would become an obstacle for them to attack each other. But this requires removing the borders to allow the free movement of people who want to live and work outside their home country. It was the idea of a strong Europe with a developed economy and labor market capable of competing with the United States, which became a new superpower after the war. The smartest European politicians immediately realized that the American Marshall Plan for financial and economic assistance to 17 European countries (including West Germany), which came into effect in 1948, was a double-edged sword. It was a kind of assistance, as a result of which Europe could become economically, and therefore politically, dependent on the United States. Looking ahead, let's say that this is exactly what happened. But then the Europeans still had the illusion that they would be able to compete economically with the Americans in the future.

A strong economy means, above all, strong people and leaders. The logic and dynamics of the workforce have given rise to the problem of standardized education especially in relation to professions that require high qualifications. This is where the initiative of the Bologna Declaration arose. All signatory countries have pledged to make their education systems similar enough to ensure the academic mobility of students, professors, and teachers of higher education. At the same time, the Bologna system, for the first time in history, gave people the opportunity to build their own individual educational trajectories — to find those very vital “guiding threads”. By studying at different universities and choosing disciplines, they became the owners of a unique continuum of knowledge and competencies, which increased their competitiveness in the national and international labor markets. It was these two advantages of the Bologna system that attracted more and more new member countries.

Despite this, the process of "Bolognaization" of Europe was very difficult and led to many unresolved issues. For example, on European and national identities, the common language of education, and the like. It took place along with other world and regional processes, which often contradicted each other such as globalization, Europeanization (de jure — transfer of sovereignty to the level of the European Union) and the upholding by countries of their own national interests: economic, political, and cultural. The ideas of cosmopolitanism as "universality plus differences", neoliberalism and the concept of "European dimension in education" became the foundation of the general ideology of the Bologna process. Today, the Bologna system is perceived by everyone as something integral and beneficial for each participating country. However, special studies show that many of the most important principles of the Bologna system are the result not of joint discussions and collective decisions, but of lobbying the interests of a particular European state or a small group of states. The rest were forced to adapt.

— Do you mean that the idea of "paradise for everyone", the idea of absolute transparency of decision-making, failed?

— Leo Tolstoy, as you know, has lines for such a case: “It was smooth on paper, but they forgot about the ravines.” How could it be otherwise? The “Bolognaization ” of higher education, first in Europe and then in a number of non-European countries, is an unprecedentedly multipurpose and internally contradictory project. There are too many different national and supranational ideologies and interests bound together in the Bologna "knot". It makes it impossible to observe the interests of each of the more than forty countries participating today in the Bologna process. As you know, one of its main goals was the Europeanization of higher education as opposed to its US-led globalization. But there was no counterbalance. Unbeknownst to itself, the Bologna Group, or rather, its most “authoritative part”, which stood at the origins of the process, became the spokesman for pro-American globalist ideals and goals, according to which higher education is mainly a preparation for a career and a “service” that can be provided for money, often for a lot of money. This conclusion is based on the fact that it is American and, most importantly, private universities — Stanford, Harvard, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology — that is the desired ideal for all universities, permanently leading the world rankings. Thus, the “ideological front line” began to run not between Europe and the United States, but between EU officials and the scientific community, which argued that higher education is much wider than just vocational training. It includes fundamental scientific and cultural dimensions, as well as social responsibility and cohesion.

— However, as you said above, today the Bologna system is perceived by everyone as something integral and beneficial for each participating country.

— It is perceived that way, yes. But it is not in reality. It looks "holistic" due to its ever-increasing bureaucratization and standardization. Moreover, these trends are most pronounced in relation to the systems of higher education in Eastern Europe, as well as countries that are not members of the EU and joined the Bologna process later. For them, the Bologna rules sound like mandatory requirements, which in fact they are not. At least until these rules are ratified by national parliaments. For the higher education systems of the founding states of the Bologna process and the countries of the “old European democracy”, the conditions are not that strict. As the ancient Romans said, “What is permissible for Jupiter is not permissible for cows.”

— It seems like the Bologna process has become unconcerned with its democratic image?

— I would say even more. The Bologna process, in a certain sense, has become an instrument of “soft” control over the previously independent national educational systems. And this is not just my opinion. There are many special studies on this topic, including international ones. In addition, the Bologna process has turned the development of European (and not only European) higher education towards undisguised commercialization.

— Considering everything you said, I want to ask, are there any goals of humanitarian value for all countries without exception that the Bologna process has achieved?

— I consider the biggest success of the Bologna Process to be its initiation of an ongoing dialogue on higher education issues, which is of decisive importance not only for Europe, but for all countries. Bologna emphasized the need for a European reform of higher education and put the University at the center of attention, giving it the opportunity to make decisions. As for the “guiding thread” learning model as building one’s own individual educational trajectory, despite its attractiveness, it is still very far from its full implementation not only in the West and in Russia, but throughout the world. Building a new identity based on a combination of common European values and national cultural traditions, declared by the Bologna Declaration, is also still more rhetorical than practical. We will try to discuss these and some other issues next time on the blog.

To be continued

The conversation was transcribed by Irina Kuzheleva-Sagan