"A person without memory is like a tree without roots. A nation that loses its memory has no future."

Daniil Granin, Soviet and Russian writer, speech at the Bundestag, 2014

"Historical memory is the immunity of a nation. A people deprived of it becomes vulnerable to manipulation and the repetition of tragedies."

Sergey Kapitsa, Soviet and Russian physicist and educator

In this edition of his blog, TSU Rector Eduard Galazhinskiy reflects on the enduring value of historical memory — for individuals, families, and the nation. He explores why preserving this memory is essential, how it should be passed on to younger generations, and the role a university must play in this process.

— Professor Galazhinskiy, what inspired you to dedicate this issue to the topic of historical memory?

There’s both a profound reason and a very specific occasion. First, we are approaching a significant milestone — the 80th anniversary of the USSR’s Victory in the Great Patriotic War. Naturally, this prompts deep reflection on everything connected to that event, which stands as one of the key pillars of our national historical memory.

Second, it was the recent visit to Tomsk by Elena Malysheva, head of the National Center for Historical Memory under the President of Russia, a member of the Public Chamber, candidate of historical sciences, and an honored archivist. She visited our university, met with students and faculty, and spoke passionately about why historical memory is more relevant today than ever before.

For our part, we showcased TSU's initiatives in this field — including our master’s program dedicated to historical memory and a data-driven research project addressing issues of collective remembrance through big data analysis. Elena Malysheva was genuinely intrigued and expressed her commitment to promoting our work at the federal level, noting that she hadn’t seen anything comparable elsewhere. In that sense, she has now become a powerful ambassador for us.

— You’d probably agree that discussing a topic like historical memory can spark mixed reactions and judgments, especially on the eve of major national holidays. Some might see such meetings as mere formalities.

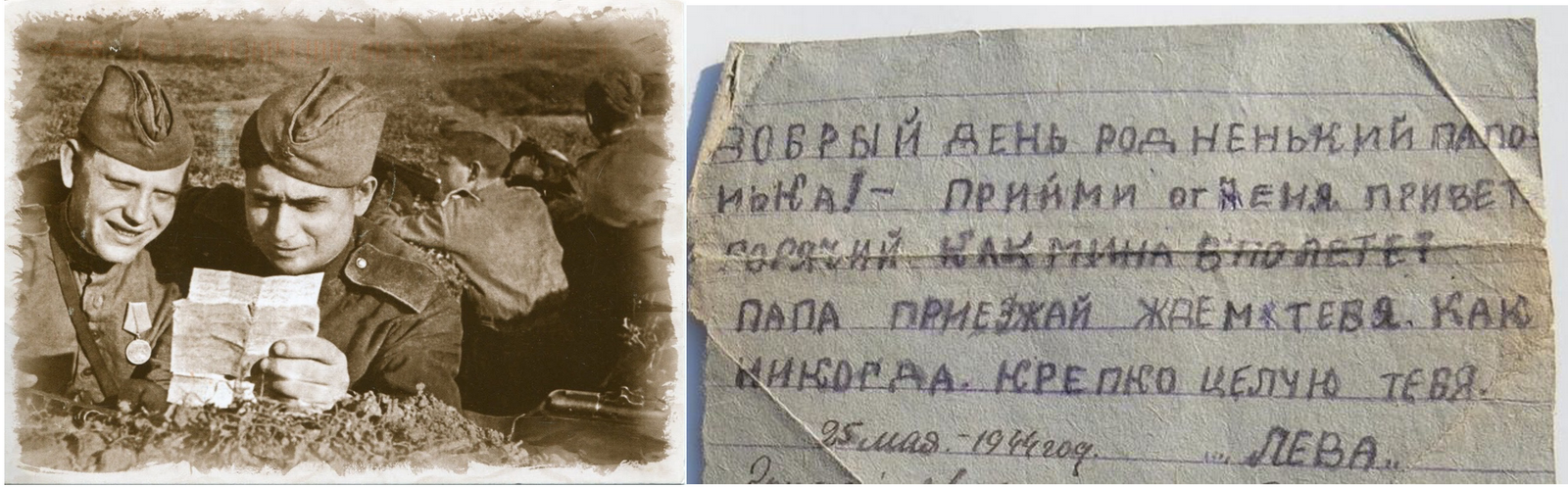

— That perspective is understandable. Yes, the 80th anniversary of Victory in the Great Patriotic War is a key state occasion, and naturally, it will be marked by official ceremonies. But it’s also a profound celebration for the entire Russian people. To this day, there isn’t a single family in our country untouched by the war — whether through the fate of great-grandfathers on the frontlines or those who contributed on the home front.

For those present, our discussion on historical memory was far fr om a ceremonial gesture — it was a meaningful conversation. After all, the classical university was conceived fr om the outset as a place for open debate. This remains one of its core purposes, carried through centuries. Today, a university stands as the number one platform for addressing the most complex and sensitive issues — those often avoided by other institutions to prevent sparking polarization, or discussed in a one-sided manner.

A classical university fosters critical thinking, encouraging us to examine topics from multiple perspectives and within various contexts. At TSU, we regularly host distinguished guests and partners — experts across a wide range of fields. Sometimes their views differ from mainstream opinions, but we know that the value of expertise isn’t measured by majority or minority approval. What matters is how accurately it reflects reality — the objective laws of nature, societal development, and alignment with moral and ethical standards.

This is exactly how we approach every challenging discussion, including the issue of historical memory. The willingness and ability to engage in such conversations is yet another hallmark of TSU — proof of our leadership role and our capacity to contribute to large-scale national priorities, such as Russia’s scientific and technological development projects.

And the more competent we become, the more high-caliber experts seek us out. For instance, in March, Russia’s Minister of Industry and Trade, Anton Alikhanov, visited Tomsk. He chose TSU as the venue for a key meeting and toured our laboratories and engineering centers. Elena Malysheva’s visit, as head of the Presidential Center for Historical Memory, is in the same vein — a recognition of TSU as a hub for serious, forward-looking dialogue.

— Earlier, you mentioned that TSU historians have already begun working on the topic of historical memory. How do you see this area developing further at the university?

— Everything related to historical memory opens up a vast field of more specific issues—many of which require immediate attention. These include concrete historical facts or topics that either naturally or suddenly rise to the forefront of public discourse—whether in mainstream media, social networks, or messaging platforms. It’s clear that the efforts of the National Center for Historical Memory alone won’t be enough to respond to all these challenges with scientifically grounded answers. That’s wh ere our university can truly make a difference.

Every such issue—or cluster of issues—is a perfect opportunity for a serious term paper or thesis project. I suggested to Elena Malysheva that the Center could "offload" specific tasks to the university. She called it a "brilliant idea." These assignments would allow our students, graduate students, and doctoral candidates to hone their critical thinking skills while maintaining both a professional and civic perspective. It’s a way to deliver practical value while contributing to the defense of historical truth. This kind of collaboration could serve as a model for a networked approach to verifying historical knowledge.

To make it work, we’ll need to unite across disciplines because today’s challenges almost always exist "at the intersection"—they demand complex, interdisciplinary expertise. TSU is ready to be an active partner in advancing the study of historical memory because we already have substantial capabilities.

For example, we know how to analyze big data—millions of digital traces across social media—to verify whether certain content reflects truth or is disinformation rooted in alien ideologies. We can monitor shifts in youth values in real time by observing trends across millions of social media accounts. The outcomes of this work are visualized through dynamic dashboards.

This is truly engaging work—operating at the intersection of knowledge and the living social fabric, which is constantly evolving under the influence of various stakeholders. Projects like these require interdisciplinary teams of cognitive linguists, psychologists, sociologists, IT specialists, and others. And I’m proud to say that such teams already exist here at TSU.

— What specific topics did you discuss during your meeting with Elena Malysheva?

— We covered a wide range of issues, and what’s important is that the conversation flowed naturally—there were no scripted speeches or formal reports. Elena Malysheva

began by illustrating how deeply personal memory is intertwined with historical memory. Her visit to Tomsk was driven not only by professional interests but also by a personal mission. While browsing the digital archives of the State Archive of the Russian Federation, she discovered three files related to her great-great-grandfather housed in the Tomsk Regional Archive. Although she knew he had spent time in Siberia, his life was mostly tied to Krasnoyarsk, and she had never encountered any references to Tomsk before. This unexpected discovery gave her another reason to visit and uncover previously unknown chapters of her family history.

Through this example, she demonstrated that historical memory is far fr om an abstract concept—it’s a deeply personal connection to meaningful events of the past. It shapes our moral compass, helping us distinguish right from wrong, truth from falsehood. It’s the foundation upon which we build our vision of the future. A nation with a strong memory knows who it is, wh ere it comes from, and what underpins its identity. Historical memory is integral to a society’s self-awareness—a collective remembrance of what truly matters.

At the same time, she emphasized that today, historical memory is often subject to political manipulation and distortion. That was the second major point she raised. By reinterpreting historical narratives, external forces can reshape public consciousness—even reprogram entire societies. A striking example is the shift in public sentiment within a neighboring state. Elena Petrovna also reminded us how, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, selective revelations fr om archival documents—stripped of context—led to distorted perceptions of Russia’s past. This had a profound impact, particularly on how younger generations viewed their own history and identity. She illustrated this with concrete examples.

For instance, not long ago, a provocative idea was circulated in Russian public discourse: that perhaps Leningrad should have been surrendered to the enemy during World War II to save civilian lives. This notion, once introduced into public debate, was designed to cast doubt on the decisions made at the time—and on the sacrifices endured. From there, it’s a short step to questioning the legitimacy of the country’s entire historical path: Did events really unfold as described in school textbooks? Was the Red Army liberating Eastern Europe, or was it occupying it? These kinds of narratives don’t appear by accident—they serve specific political agendas.

That’s why it’s critical not to accept such narratives at face value but to ask: Why is this being promoted? What’s the true objective behind these reinterpretations? The answer is clear: to undermine trust in the Soviet Union’s role in defeating Nazism, to sow division within society, to equate Stalin with Hitler, to blur the line between aggressor and victim—and, ultimately, to strip the nation of yet another cornerstone of its historical identity.

When these ideas take root in the public consciousness, even well-established historical facts become tainted with negativity. The goal is to reshape a society’s understanding of its past—and, by extension, to alter national consciousness. History has shown us that such transformations inevitably lead to the erosion of statehood. That’s why defending historical memory is not just important—it’s a strategic imperative.

This importance is reflected in Russia’s legal framework: the term "historical memory" is enshrined in the Constitution and referenced in key strategic documents. The focus is understandable—in an era of open information flows and deliberate distortions of history by Western nations, Russia faces ongoing attempts to rewrite core national values and broadcast these revisions globally. We see this vividly in the dismantling of Soviet war memorials abroad—acts that are now recognized as part of an information war.

The only way to counter this is by preserving historical memory and asserting our historical sovereignty—the right to interpret our past, define its meaning, and uphold the values tied to our historical experience. Elena Malysheva cited another example: the ongoing Western reappraisal of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. In the West, it’s often portrayed as an act of betrayal and a trigger for World War II. In contrast, the Russian perspective frames it as a necessary diplomatic move, buying critical time for the USSR to prepare for the inevitable conflict.

In this way, historical memory forms the bedrock of historical sovereignty—without it, sustainable development for both state and society is impossible. Historical memory isn’t about "yesterday"—it’s about "tomorrow."

— Were there any topics discussed that you would consider particularly relevant or "special" for a university audience?

— One such topic was the understanding of historical memory as a scientific category. It was pointed out that this concept has been extensively developed not only in Russia but also in the West, wh ere a whole network of institutions is dedicated to issues of national memory. However, it was also noted that Western academic approaches to historical memory are often shaped with a keen awareness of current geopolitical interests.

An example of such a politicized approach can be found in the works of American historian and Yale professor Timothy Snyder, translated into Russian, including Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin and The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America. Snyder is known for his quote, “History is a shield against propaganda. Wh ere memory is burned, lies settle in.” However, throughout all of Snyder’s works—despite covering different periods and topics—there is a consistent narrative: the history of Russia is portrayed as a history of constant expansion and authoritarianism.

According to Snyder, Russia has always been and remains a fascist state, changing only its forms but not its essence. This view is most vividly expressed in The Road to Unfreedom, which is less a historical study and more a work of political analysis. Snyder accuses modern Russia of interfering in global politics, including U.S. elections, and draws parallels between Russia’s actions in the 21st century and the policies of fascist regimes in the 20th century.

His key arguments rely on historical examples—such as the partitions of Poland, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the annexation of Crimea, and the events in Donbas—which he interprets as parts of a single expansionist strategy by Russia. Snyder uses historical facts and interpretations for political purposes, evident in his creation of ideological labels like "red fascism" and his attempts to cast both Russia's past and present in a specific ideological light.

He overlooks complex historical and cultural processes that took place in Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine, replacing them with straightforward accusations against Russia. For instance, Snyder contrasts the Soviet Union with a "civilized" Poland, omitting facts about Polonization, ethnic cleansing, and the suppression of Belarusian and Ukrainian identities within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and interwar Poland.

Snyder introduces concepts like the "politics of inevitability" and the "politics of eternity," framing the "progressive" path of the West against Russia's "cyclical" history. These concepts serve as explanatory models for the current global conflict between liberal democracy and Russian authoritarianism. He links modern political events—such as Trump’s election victory in the U.S. or Lukashenko’s actions in Belarus—to those of the USSR and the Russian Empire, constructing an image of a "perpetual fascist threat" from Russia.

Snyder’s works belong more to the realm of historical politics than to academic historiography. They create the image of an enemy aligned with Western geopolitical narratives and contribute to the formation of a Russophobic discourse.

Based on the article by E.V. Kodin, Modern History According to Timothy Snyder https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/noveyshaya-istoriya-po-timoti-snayderu )

In the Russian academic tradition, historical memory is viewed as a phenomenon grounded primarily in fundamental scholarly knowledge. Professional historians play a central role in this process: they are the ones responsible for defining key priorities, interpreting events, and shaping meaning. The foundation for this work lies in archival documents—verified sources of information that allow us to distinguish genuine history from distortions. Only a comprehensive analysis of a body of archival material provides the opportunity to speak of historical truth.

There is another unique element within Russia’s national model of historical memory, something absent in most other countries — the tradition of family and intergenerational transmission of experience. The memory passed down orally within families preserves personal narratives and value-based orientations, creating a vital link between generations. It is precisely this combination of three components — academic scholarship, archival authenticity, and familial memory — that makes historical memory a resilient and coherent system. This system is especially crucial in today’s complex information landscape.

Interest in history is on the rise: people are increasingly drawn to local studies, genealogy, and exploring the history of their native regions. However, most of these individuals lack the necessary academic tools to properly interpret what they find. As a result, information is often consumed in fragments, stripped of its broader context. People encounter a single document or isolated fact and accept it as the definitive truth. This fragmented perception leaves individuals particularly vulnerable to manipulation. The only way to navigate this vast flow of information correctly is by relying on scholarly knowledge, recognizing the priorities of historical memory, and understanding the core values that underpin it.

— How did the students respond to the discussion with the head of the National Center for Historical Memory? Were there any questions, and if so, what were they about?

— The students responded thoughtfully and appropriately. And they didn’t shy away from asking difficult questions. I recall a question about strategies for preventing disinformation and how effective—or ineffective—blocking harmful information resources truly is in that regard. One young man raised a question about the Katyn massacre, suggesting that this historical event is portrayed "too one-sidedly" in public discourse. Another question came from a future history teacher, who asked how to accurately teach schoolchildren about World War II without violating Russian laws prohibiting the use of Nazi symbols and insignia. Elena Malysheva answered all these questions thoroughly and professionally.

— You’ve already pointed out that young people are particularly vulnerable to accepting fragmented historical knowledge. But is this solely due to their inexperience and lack of understanding of history as a consistent and interconnected process?

— Of course not. As we know, young people make up the largest and most active audience on social media. And here’s an important point: when discussing social networks, the focus is usually on their limitless potential for communication, socialization, solidarity, information sharing, education, business development, volunteering, and so on. Much less frequently do we talk about the equally boundless potential of social media as a breeding ground for disinformation, fake news, manipulation, and similar threats.

Monitoring public opinion among youth reveals significant polarization. Experts explain that today, this effect is largely driven by social media platforms. Young people, often without realizing it, find themselves trapped within so-called "information bubbles." The algorithms feed them content—both in type and volume—that reinforces their existing beliefs, making them think this is the dominant narrative, the prevailing public opinion. This constant reinforcement of what a person already likes or is predisposed to believe gradually narrows their worldview. It creates the illusion that "everyone" is talking about the same thing and evaluating it in exactly the same way.

— What other major challenges and risks do you personally see when it comes to historical memory?

— As both a historian and a psychologist by education, I find one particular issue especially critical—and it represents a colossal risk: the potential use of scientific methods and experimental results to deliberately falsify historical memory.

Many people may not be aware, but there have already been numerous scientific experiments involving the implantation of false memories into individuals’ consciousness. Adults were repeatedly "reminded" of childhood events that, in reality, never happened. These suggestions were delivered skillfully, woven into genuine memories recalled by the participants themselves. The outcome? People began to sincerely believe in experiences that never took place.

These experiments were conducted for legitimate scientific purposes. However, they demonstrated just how easily such techniques could be exploited by unscrupulous actors to develop targeted methods of manipulating consciousness and memory—an especially dangerous prospect in today’s era of post-truth and competing versions of "truth."

For reference:

Scientists from the UK and Germany have not only succeeded in implanting false memories into people’s minds but, for the first time, have also safely removed those memories without affecting genuine recollections of the past. While this discovery may sound like science fiction, it is grounded in real laboratory experiments. Researchers hope that this new method could be applied in fields like criminal justice—particularly during the interrogation of witnesses and suspects.

Human memory is incredibly fragile: even mild external influence can alter how a person perceives their own experiences. For example, if an authoritative source repeatedly presents certain information, even the most critically-minded individuals may eventually accept it as truth. This can lead to vivid "memories" of events that never actually occurred.

In the study, scientists worked with a group of 52 volunteers. With the help of the participants’ parents, they implanted plausible yet false childhood memories—such as recalling a car accident that never happened. These fabricated memories were blended with real events, enhancing their perceived authenticity. By the third round of interviews, 40% of participants began recounting these fictional events as if they were genuine experiences.

The next phase of the experiment focused on erasing those false memories. Researchers employed two strategies: The first involved educating participants about how memory works and explaining that false memories often stem from external suggestions. The second highlighted how repeated questioning can trigger fabricated recollections. Participants were then encouraged to re-evaluate their memories in light of this new understanding.

The results were remarkable: the number of false memories dropped significantly, while genuine memories remained intact. Importantly, the scientists emphasized that no technical or biological interventions were used—only knowledge and awareness.

(Source: https://www.vesti.ru/article/2541600)

Scientists have identified several phenomena related to human memory as a form of mental activity and a kind of "time travel," which can also influence historical memory. For instance, when a person recalls events from many years ago, the brain may unconsciously replace older memories with more recent episodes. This happens because the brain strives to adapt to current reality, favoring memories that feel more relevant to the present. Researchers emphasize that our memory is nothing like a video camera—it doesn’t preserve information in an unchanging state. On the contrary, the brain is constantly "editing" memories, reshaping the past to better align with today’s worldview.

This process takes place in the hippocampus—an area of the brain that scientists liken to a film editing studio, capable of adding "special effects" or altering the "soundtrack" of our recollections. As a result, a person might unintentionally provide distorted information—not out of malice, but because their hippocampus has already modified the memory to fit their current perspective. Such effects must be carefully considered when working with witnesses to historical events.

Finally, there’s another psychological feature that significantly impacts how people form—or alter—their historical memory. Numerous studies have shown that even blatantly false information can come to be perceived as credible if it is repeated often enough and comes from multiple sources. In today’s world of information overload—with a constant stream of data from media, television, and the internet—this issue is more pressing than ever.

The danger of such disinformation lies in its frequent appeal to basic human emotions—fears and hopes. While many believe they are immune to the influence of false messages, evidence suggests otherwise. As far back as the 1940s, psychologists observed a clear pattern: the more frequently a rumor is repeated, the more convincing and "truth-like" it becomes. This effect arises because rumors spread from person to person, eventually taking on the appearance of "public opinion."

Later, in the 1970s, a series of experiments with students reinforced this idea. Participants were asked to assess the credibility of certain statements, some of which were deliberately false. When those same statements were repeated after some time, participants began to accept them as true—even without additional evidence. Similar experiments conducted in the 2010s confirmed that mere repetition increases the likelihood of information being perceived as accurate. In other words, even if someone knows a statement is false, frequent repetition raises the chances that they will eventually begin to believe it.

– So, the main risks of historical memory falsification are tied not only to legitimate scientific experiments—when their outcomes are exploited by bad actors—but also to the very nature of human psychology?

– That’s true, but it doesn’t stop there. The relentless technologization of our digital society, along with the unfolding phenomenon of technological singularity—where technologies themselves begin generating next-generation technologies—has presented us with a unique double-edged gift: artificial intelligence, evolving at an exponential rate. AI has become, by all indications, a fundamental or cross-cutting technology of the current digital age—and likely of future stages as well—since AI is now embedded, in some form, within nearly every modern technology, regardless of the field.

When it comes to shaping historical knowledge and memory, AI’s dual nature reveals itself clearly: it holds both constructive and destructive potential—and both are virtually limitless.

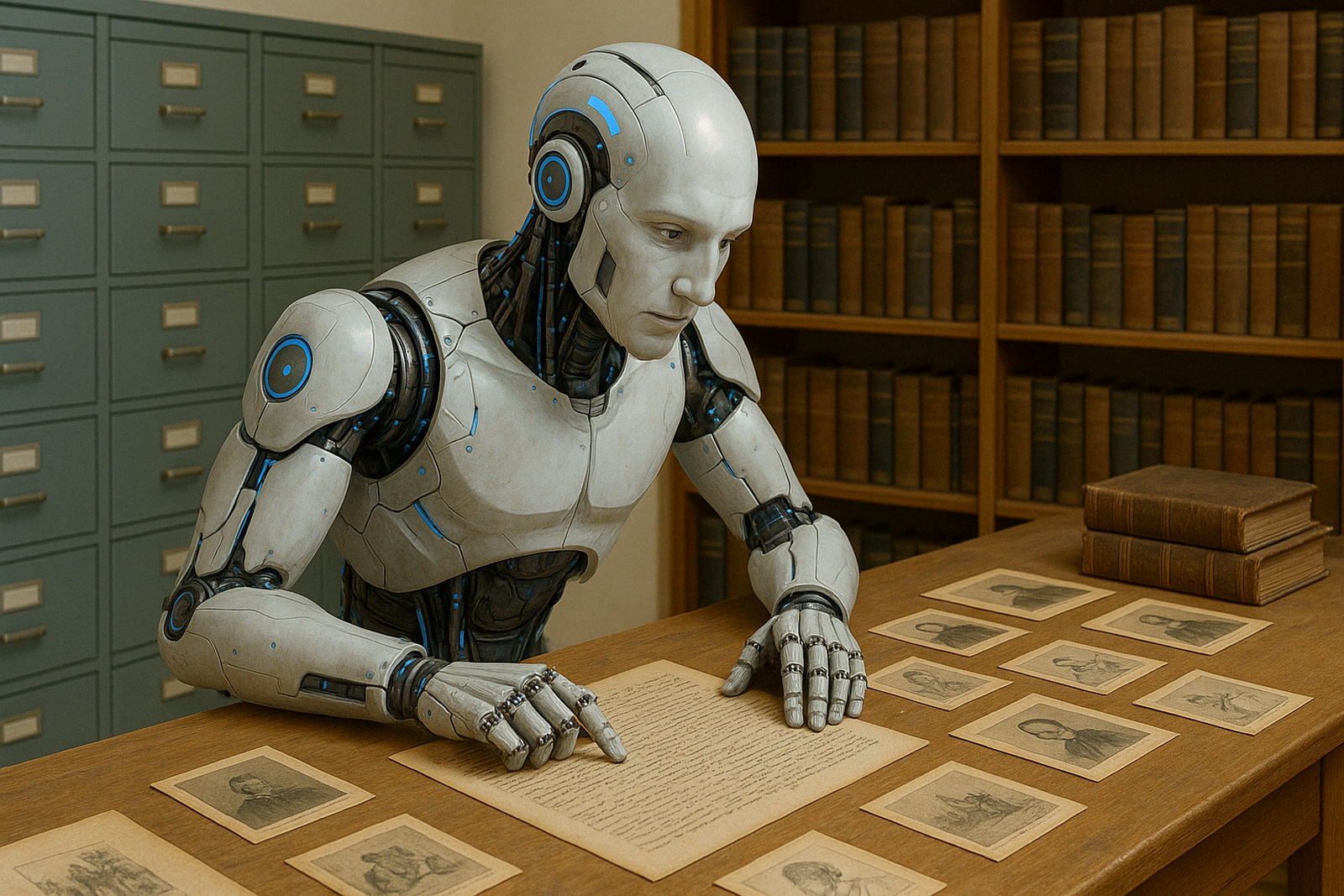

On the constructive side, AI can revolutionize the preservation and accessibility of historical memory by creating unified digital archives and searchable databases. Neural networks can process and cross-reference enormous volumes of historical data—from newspaper archives to confidential correspondence—identifying hidden patterns, causal relationships, and cycles of societal development. This allows for a more precise analysis of historical causes and effects, crises, regime changes, and so on. In short, AI enhances the objectivity and depth of historical source analysis.

AI can also read handwritten or cursive texts, including ancient manuscripts, and even reconstruct missing fragments of documents or poorly preserved artifacts—effectively "completing" historical narratives. As an indispensable assistant in deciphering ancient texts and cross-referencing diverse sources, AI opens entirely new vistas into the past.

Modern AI-driven projects, combined with virtual reality, are now capable of creating immersive reconstructions of historical events—bringing history to life in ways that deeply engage both emotions and intellect, particularly in educational contexts. AI can recreate historical landscapes, simulate dynamic models of key events—be it military battles, revolutionary uprisings, or broader patterns of civilizational development.

Interestingly, some scholars foresaw this potential decades ago. French historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, for example, famously predicted over sixty years ago that "the historian of tomorrow will be a programmer, or he will not exist at all."

For reference:

For many years, the study of Peter the Great—one of Russia’s most prominent historical figures—was hampered by the slow pace of publishing his handwritten legacy. One of the main obstacles was the emperor’s notoriously illegible handwriting. To accelerate the integration of Peter’s manuscripts into academic and public discourse, the Russian Historical Society, together with Sberbank, launched the "Digital Peter" project. This initiative focuses on decoding the tsar’s autographs using cutting-edge information technology. Thanks to artificial intelligence, Peter I’s cursive documents have been transcribed with an impressive accuracy rate of up to 97%.

https://historyrussia.org/proekty/digital-pjotr.html

On the other hand, given that AI algorithms are trained on available datasets, if those datasets contain biases or propagandistic narratives, AI will inevitably replicate and amplify these distortions—presenting them as so-called "objective knowledge." Artificial intelligence has already mastered the creation of fake historical documents, meticulously styled to mimic authentic sources—even down to handwriting imitations, period-specific fonts, and linguistic turns of phrase. This dramatically increases the risk of intellectual disinformation and manipulation of historical knowledge.

Even the most advanced generative language models lack true comprehension of content in the human sense. They process text statistically, not conceptually, which can lead to logical inconsistencies and false conclusions. If the analysis of historical data becomes subordinated to a single ideological agenda or corporate interest—whether through state-run platforms or global tech giants—it could result in the artificial reshaping of collective memory.

With increasing automation and the pervasive integration of AI into daily life, there is a real danger that human capacity for critical evaluation of historical information will erode. This would inevitably lead to a superficial or distorted understanding of complex historical processes.

"The paradox of technological advancement in the realm of knowledge acquisition lies in the fact that as humans develop artificial intelligence (AI) and enhance its cognitive capabilities—through machine learning and the construction of neural networks as a functional core of deep AI processing—humans themselves gradually begin to lose these very cognitive skills."

(A.A. Strokov, The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Preserving Historical Memory: Philosophical and Legal Aspects, Legal Science and Practice: Bulletin of the Nizhny Novgorod Academy of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia, 2022, No. 1 (57), p. 282)

— How can we minimize all these risks?

— I believe there are at least two main paths forward. The first is the development of legal frameworks to govern the use of artificial intelligence in scientific activities—and in non-scientific spheres as well. This includes refining AI regulatory codes. A good reference point here could be Isaac Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics, formulated back in the mid-20th century. At present, Russian law lacks clear mechanisms for regulating AI's role in preserving and transmitting historical memory. This creates risks of misinterpretation or even "privatization" of historical knowledge. The conclusion is simple: AI must remain a tool for historians, not a judge of history. Its capabilities should be applied thoughtfully, always in combination with classical methods of socio-humanitarian analysis, and with a firm understanding that moral responsibility for research outcomes lies with the scholar—not with artificial intelligence.

For non-historians, it’s crucial to remember that when turning to AI for answers about historical matters, they risk receiving either fundamentally inaccurate information or responses shaped by a particular ideological lens. Young people, accustomed to seeking instant answers from neural networks, rarely stop to question this. The danger is that, over time, falsified historical narratives could overpower academic historical knowledge, effectively erasing a nation's authentic historical memory. With all this in mind, I would say that historians today are truly "soldiers on an invisible front line," and the discipline of history—especially the study of historical memory—has never been more vital to societal survival and national sovereignty.

The second key to reducing AI-related risks in handling history is to strengthen the human factor itself: fostering and reinforcing critical thinking as the primary safeguard against falsehoods of any kind. We all witness how, in this era of post-truth and postmodernism, the concept of truth is becoming blurred and fragmented. Engaging with knowledge and truth under such conditions is a major challenge—one we strive to meet with dignity within the walls of our universities. But it is also a challenge to our national identity and the resilience of our historical memory.

After all, the classical university was established precisely as an institution dedicated to upholding such core values. I believe that in these complex postmodern times, universities must become the centers for verifying and advancing historical knowledge—institutions upon which society can rely. Moreover, universities should serve as hubs for public enlightenment in history, spreading accurate historical understanding as widely as possible.

Rector of Tomsk State University, Eduard Galazhinsky,

Member of the Presidential Council for Science and Education of the Russian Federation

Vice President of the Russian Academy of Education

Vice President of the Russian Union of Rectors

Interview conducted and reference materials compiled by Irina Kuzheleva-Sagan