This issue of the blog is dedicated to a new large-scale project by Tomsk State University: the establishment and development of a multi-profile experimental farm in the Republic of Altai. Rector Eduard Galazhinskiy discusses the immediate and long-term plans related to this project.

– Professor Galazhinskiy, today's discussion topic might come as a surprise even to many TSU staff members, let alone the external audience. How did our university come to acquire an experimental farm covering an area of 68,000 hectares in the Republic of Altai? It reminds me of the old Soviet movie A Noisy Household.

– I can't say that these associations are entirely incorrect. The “household” is indeed very complex. However, this project didn't happen "all of a sudden." Intensive work on it has been ongoing for about three years. We didn't discuss it publicly because there were too many uncertainties. Gradually, these uncertainties are being resolved, perspectives are becoming clearer, serious partners are emerging, and now we can — and should — talk about it.

– How did this project come about?

– It all began with a proposal fr om Academician Valentin Parmon, the chairman of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. The idea originally belongs to him. Academician Parmon approached me several times regarding this matter. The Altai Experimental Farm was established in the village of Cherga at the initiative of the outstanding biologist and geneticist, Academician Dmitry Belyaev, who was the long-time director of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics of the Siberian Branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences. He worked on the conservation and breeding of rare, endangered animal breeds. This direction continued the ideas of Academician and geneticist Nikolai Vavilov regarding the study of ancient indigenous genotypes in the animal and plant worlds. Thus, from its very inception in the late 1970s, this farm was under the jurisdiction of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. There were even plans to create an "Academic Town 2.0." With the passing of Academician Belyaev, the main driving force of the project, the development of this advanced farm began to slow down. After the collapse of the USSR, it rapidly regressed into an ineffective "collective farm." A few years ago, the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation attached the Altai Experimental Farm to the Federal Altai Scientific Center for Agrobiotechnology (Barnaul), but this merger didn't lead to significant acceleration in the farm's development, despite its enormous potential.

– In other words, three years ago, the experimental farm still needed effective management?

– Exactly. Academician Parmon was very concerned that, since the 1990s, serious scientific work had been effectively frozen there and economic activities had stalled. Something urgently needed to be done to prevent everything from falling into disrepair. Naturally, I wondered why this important proposal was made to TSU, rather than, say, Novosibirsk State University. It turned out that NSU had already been approached, but they hesitated to take on the management of the territory due to a lack of necessary material and organizational resources, as well as appropriate scientific directions.

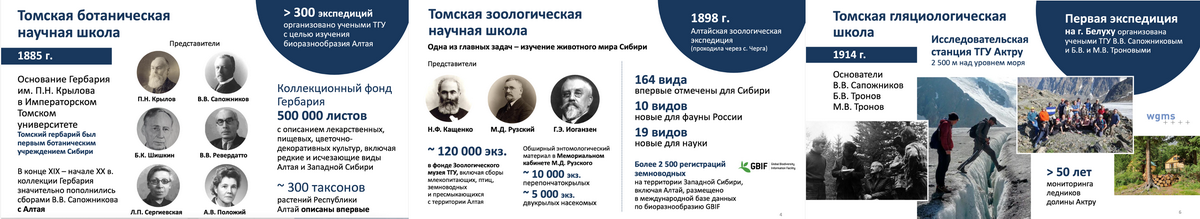

At TSU, we have such directions, including studies in climate and ecology, with the creation of a carbon polygon, and agrobiotechnology. Additionally, we have long-established scientific schools in botany, geology, and glaciology. If we consider the broader prospects for developing the Altai territory, there's much for our chemists, archaeologists, philologists, economists, and even astrophysicists to engage in. And it's not just about them. Beyond science, this project also encompasses education, as various practical activities can be organized for undergraduate and master’s students across all these fields. The economic potential, with proper management of all natural resources, could also be substantial, including the production of eco-friendly products, scientific tourism, recreation, and sports.

When it comes to the material resources necessary for the proper utilization of this invaluable territory, no single entity, and certainly no university, possesses them alone. From the very beginning, we understood that strong partnerships would be essential. However, committing to such a risky yet incredibly promising venture was not an easy decision to make. Therefore, TSU organized a special working group to discuss all the risks and prospects of the Altai project. I cannot say that everyone was unanimously in favor, but ultimately, we accepted this proposal, which, by the way, was immediately supported by the Ministry of Science and Education of the Russian Federation.

– What arguments, aside from those already mentioned, were particularly important to you in supporting this decision?

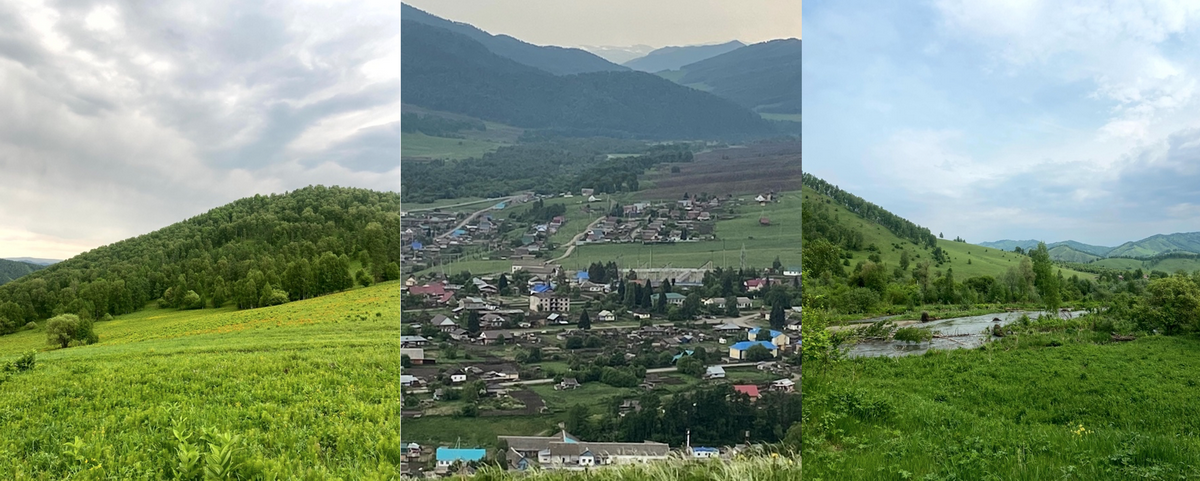

– There were two additional arguments: one subjective and one historical. The subjective argument relates to the personal impression I gained directly from the territory in question. Such beauty and diversity cannot leave anyone indifferent. I don't know if there are any other places in our country that combine so many different natural landscapes: from semi-deserts, swamps, and forest-steppes to vast deciduous and coniferous forests, as well as mountain ranges reaching heights of up to 4,000 meters above sea level. Plus, there is a rich variety of fauna and avifauna. Experiencing all of this feels like stepping into a portal to another realm.

The historical aspect of the project is equally captivating: the first scholars who seriously and systematically studied this Altai territory were scientists from the Imperial Tomsk University! More than a hundred years ago, professors from Tomsk built their dachas in Cherga. Among the pioneering researchers of Altai, I refer to one of the first rectors of our university, Professor Vasiliy Sapozhnikov, a botanist, glaciologist, geographer, traveler, photographer, and author of several works on Altai; as well as the Tronov brothers – MikhailTronov, a geographer and glaciologist, and Boris Tronov, a chemist, who were also authors of books about Altai. The travels, ascents, research, and descriptions of expeditions to Altai by these remarkable pioneering scientists, climbers, and extraordinary enthusiasts form some of the brightest pages in the history of the Tomsk Branch of the Russian Geographical Society and TSU itself.

The persistence with which these individuals pursued their scientific goals is still impressive today. For example, when Professor Sapozhnikov was denied funding for another expedition to Altai, despite its undeniable relevance, he started raising money for it by giving popular science lectures about his first Altai expedition. He delivered these lectures not only in Tomsk but also in Irkutsk, Omsk, Barnaul, and other cities in Siberia. Remarkably, in the late 19th century, such talks about travels, complete with illustrations and photographs, were immensely popular among the ordinary residents of Siberian cultural centers, with people eagerly purchasing tickets as if they were going to the theater.

For your information: By the end of the 19th century, Altai already had a history of over a century of study and a series of prominent names: Humboldt, Pallas, Gebler, Yadrintsev, Potanin. However, most research focused only on the peripheral areas of Altai. The lack of transport routes and the preconceived notion that central Altai differed little from its outskirts hindered deeper exploration of the mountains. The task of debunking this misconception fell to Vasiliy Sapozhnikov.

Summarizing the results of the 1895 expedition, he wrote: "The very first journey, during which I tangibly encountered the nature of Altai, revealed the main goal I should strive for. Traveling from Lake Teletskoye to the Bukhtarma Valley, I was vividly convinced of how incomplete our acquaintance with Altai was, and it was then that I outlined the areas of my future work." A typical day of Sapozhnikov's expeditions began very early. The usual daily trek covered 30-40 km, taking between 6 to 8 hours. The results of Sapozhnikov’s four years of work in Altai astonished everyone, as they brought new discoveries to Russian geographical science and disproved previous misconceptions about this mountainous region. For instance, the belief in the insignificance of glaciation in Altai.

In total, Sapozhnikov discovered, documented, and mapped about 50 glaciers in Russian Altai, covering an area of over 200 square kilometers. He grouped the discovered glaciers into three glacial centers: Belukha, Northern Chuy, and Southern Chuy. Additionally, Sapozhnikov collected extensive samples of rocks and minerals, documented various plants, sketched numerous animals and birds, took several thousand photographs, and preserved their glass slides. He also described potential tourist routes. Sapozhnikov's discoveries attracted the attention of scientists from other disciplines, including the world-renowned Russian and Soviet geologist and science fiction writer, Vladimir Obruchev, who visited Altai in 1914.

The monographs detailing Sapozhnikov's Altai expeditions became indisputable achievements in scientific and geographical literature, while his guidebook to Altai remains unmatched to this day. All the books were written in an engaging style, based on factual materials, and richly illustrated with his sketches and photographs, the scientific and historical value of which is immense. Despite his busy schedule, he personally colored the slides. Unsurprisingly, Vasiliy Sapozhnikov's books became widely known and received high accolades not only in Russia but also abroad.

The Feat of the Tronov Brothers

In the summer of 1914, the epicenter of attention was Altai, wh ere news spread fr om the highest natural antenna in the center of Eurasia about the ascent of the highest hypsometric point of the Altai Mountains — Belukha. The heroes of this ascent were two Russian brothers from Siberia, Boris and Mikhail Tronovs. Their first ascent to the highest "roof" of the Altai Mountains marked a remarkable triumph in the exploration of the world of eternal snow and ice in the cold, lifeless alpine region. This event undoubtedly set a new direction for the study of the nature, history, and culture of Altai and Siberia, elevating the status, scale, and significance of Altai among the world's mountainous regions.

For centuries, Belukha has served as a unique natural screen reflecting various periods of human evolution. Evidence of this is seen in the ancient Paleolithic human habitation sites discovered in the valley of the right tributary of the Katun River by archaeologists from Russia and Belgium in the early 21st century. Belukha is the largest ice reservoir and a gigantic thermos of ice water in Russian Altai. From the slopes of the massif flow 169 glaciers, comprising over 60% of the glaciated area of the Katun Ridge.

After the ascent of Belukha, the Tronov brothers' paths diverged. Boris became a renowned chemist, Doctor of Sciences, Professor, working at Tomsk State University and Tomsk Polytechnic University. Mikhail devoted himself to glaciology and climatology, discovering over 600 glaciers in Altai. In 1950, he was awarded the Stalin Prize for his book Essays on Glaciation of Altai. His scientific achievements were published in 250 works, including 15 monographs. For his contributions to glaciology and climatology, he was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labor and the Large Gold Medal of the Geographical Society of the USSR in 1972. At Tomsk State University, he established a scientific school of glaciologists and climatologists.

The Tronov brothers left a lasting legacy in the study of modern glacier energy, the interrelations of climate and glaciers, and the hydrological and hydrochemical processes shaping landscapes, with a particular focus on the Altai region. It was under Mikhail Tronov's initiative that research began in the Aktru Valley, wh ere for more than 30 years, the TSU Aktru station has been conducting continuous monitoring of glacier dynamics.

(based on https://risk.ru/blog/203565 ; https://news.tsu.ru/news/zapomnyat_nashi_imena/)

– Such individuals, historical events, and facts truly deserve to be known and remembered by future generations, today’s students, and scholars of Tomsk State University.

– Absolutely. A deeper immersion in these contexts—scientific, educational, economic, and cultural-historical — has led to a conscious desire to complete the gestalt, as psychologists would say. Tomsk Imperial University was at the forefront of the scientific study of Altai, and who better than Tomsk State University to continue this important work?

– What stage is the Altai project currently at?

– We are at a stage that requires simultaneous work across several directions. Firstly, we are engaged in ongoing communication with the government of the Republic of Altai. Since early June, Andrei Turchak has taken over as the acting head of the Republic. He is a highly experienced federal-level leader, a proactive individual with a dynamic approach. We have already met with him to discuss potential collaboration within the Altai project. To clarify, the land being transferred to our management is federal property. Together with the government of the Republic of Altai, we are working on solutions that will, on one hand, address the concerns of the Republic's residents regarding the effective use of the territory transferred to TSU, and on the other hand, facilitate the achievement of the scientific and educational goals of our university in this area. There is also a broader context of state interests that must be fulfilled within this project. Therefore, we have agreed on a joint audit of the land’s utilization and the alignment of university projects with the development plans of the Republic of Altai. Once we consolidate all these contexts, we will present our combined solutions to the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation for final approval.

The second area of work at this stage involves various calculations and planning, familiarization with the territory, and the people directly working at the experimental farm, including their employment as TSU staff, auditing the farm itself, and more. This entails the preparation of a vast amount of documentation and correspondence with various state and non-state entities involved in the management of the experimental farm and the territory it occupies. The land being transferred to us, this invaluable asset, was previously divided into more than 500 plots, each representing a separate object for management. This necessitates inventorying, technical descriptions, legal formalization, as well as justifying what exactly we plan to accomplish on this land.

All of this is complicated by the fact that some of the land is already developed. We now need to reverify the legality of all decisions made regarding the lands previously overseen by the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. We have to engage in all these processes, and at times it feels like it might be easier to conquer Mount Belukha than to navigate through this 'ninth wave' of legal and bureaucratic paperwork, along with the formal procedures related to the transfer of the Altai Experimental Farm to us. I want to emphasize that the Altai Experimental Farm has officially become a branch of Tomsk State University.

Finally, there is one more extremely complex area of work that we are currently engaged in. This is the direct management of the experimental farm in Cherga. Along with the land, we have been entrusted with the care of over 3,500 animals. These include both domesticated animals (cows, sheep) and wild ones (bison, marals, deer, and others). It was crucial to establish a seamless operation for their care. They all require summer pastures and winter feed. Therefore, concurrently with everything I have mentioned, we conducted planting. Thanks to the heroic efforts of the farm workers (now our TSU staff), tens of thousands of hectares of land were sown, ensuring the sustainability of the Altai Experimental Farm and its preparedness for the upcoming winter. However, caring for the animals involves more than just feeding and grazing. It includes milking, veterinary care, and other specific needs depending on the types of animals. Additionally, we needed to master a specific financial accounting system that operates within academic agricultural institutions with their own experimental farms. We are just beginning to tackle this, as we have never dealt with it before. We must seek and attract professionals for this purpose, which is also quite challenging. Thus, alongside constant negotiations, meetings, consultations, and the processing of countless documents, there is substantial hands-on work "on the ground."

– Who is overseeing all these areas of work on behalf of TSU?

– A special working group is managing the project from TSU. This group includes not only our university’s lawyers, financiers, and economists but also staff with significant organizational experience and, of course, scientists representing the main research directions we plan to develop in the Altai territory.

Among them are PhDs, professors, and heads of relevant departments at TSU. The team includes Alexander Vorozhtsov, acting vice-rector for scientific and innovative activities at TSU; Sergey Fedko, who has been appointed director of the Altai Experimental Farm TSU branch; Konstantin Surikov, director of the experimental farm; Danil Vorobyov, director of the Institute of Biology, Ecology, Soil Science, Agriculture, and Forestry; Mikhail Yamburov, director of the Siberian Botanical Garden of TSU; Platon Tishin, dean of the Geological and Geographical Faculty at TSU; Kirill Golokhvast, head of the Agrobiotech Advanced Engineering School at TSU, and other specialists. They are not only experts in their fields but also individuals who know and love Altai well. For instance, TSU chemist Professor Lyudmila Borilo, who is currently managing several important aspects of the project, once conquered Mount Belukha herself a few years ago.

– Have there been any thoughts that this entire project, despite its initial appeal, might turn out to be too burdensome for TSU?

– I won’t hide that various concerns have arisen and continue to arise. However, in this case, the goal truly justifies the means. As I mentioned earlier, we understood from the very beginning that our university alone could not manage this project. Therefore, we immediately began seeking strong partners who shared our enthusiasm and with whom we could implement the most innovative and revolutionary initiatives in this territory: various experiments, technologies, infrastructure development, and production.

Moreover, our university’s presence in this area extends beyond the pioneering efforts of Sapozhnikov and the Tronov brothers. In a certain sense, TSU has been connected to this territory for over 120 years, training specialists for it. The Republic of Altai is developing dynamically and has a significant need for scientific support for its growth.

A few years ago, while traveling to our Aktru station, I unexpectedly visited the former head of the Ongudai District in the Republic of Altai, Miron Babaev, who is also a TSU graduate. For 30 years, he has systematically sent school graduates from his district to our university, exemplifying how talent retention in the area is managed. In his office, I saw old black-and-white photographs of the rector of the Imperial Tomsk University, Vasiliy Sapozhnikov, with a local guide during his ascent of Mount Belukha. This guide was Miron Babaev’s grandfather. I am confident that the long-standing "Tomsk trace" can be found in nearly every district of the Republic of Altai.

Thus, TSU has been deeply connected to the Altai land, its history, and its culture in various ways for over a century. This connection confirms that the Altai project is not incidental for us. One could say it was, in a certain sense, predestined for us. This awareness, along with the realization of the immense potential opportunities of the Altai project, keeps us motivated and reassures us about the endeavor we have undertaken.

– And yet, what can the Altai experimental farm offer TSU that would outweigh all its material, time, and moral costs? Of course, this goes beyond purely scientific results reflected in relevant scientific reports, articles, and publications.

– The Altai experimental farm represents a significant and unique investment for our university. TSU is not entering this venture merely as an agricultural entity but primarily as a custodian of scientific knowledge and a developer of modern technologies for producing high-quality, essential products. The combination of our expertise with the magnificent ecology of Altai holds the promise of equally magnificent results. This includes advancements in animal husbandry, crop production, and the cultivation of medicinal herbs. Historically, cattle have grazed freely, and medicinal herbs have thrived in the elevated terrains of Altai without chemical intervention. By applying our existing agrobiotechnology expertise to these conditions, TSU has the potential to become a leader in the production of innovative and ecologically pure products.

We are currently investing in this venture to achieve greater returns in the future. Within the consortium of partners, TSU acts as both the steward of the land and livestock and the developer of new technologies. An innovative center is planned, which will include the establishment of a biobank with DNA samples from plants and animals, including endangered species. Currently, such a biobank exists only at Lomonosov Moscow State University. We will also develop digital genetic platforms — databases for breeding and hybridization. Specialized monitoring systems will be implemented for tracking climate gases and the health of the Cherga River basin, using advanced technologies like carbon monitoring, hydrological assessments, unmanned aerial systems, and AI-driven innovations. These systems will enable precise monitoring of animals and plants based on their elevation. All of this requires thorough study and documentation.

The key idea behind the Altai project aligns with the creation of a Higher School of Agrobiotechnology at TSU. This includes opening and licensing new educational programs, particularly in veterinary medicine and animal husbandry. A revolution is underway in modern agriculture, driven by new technologies that are transforming the field. This includes the digitization of processes, big data analysis, artificial intelligence, new materials, genetic tools, and UAVs. Consequently, new challenges are emerging for the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation. TSU is at the forefront of this transformation.

In this vision, the Cherga region serves as a vast testing ground for scientific experiments, workforce training, and technological trials aimed at achieving a critical strategic goal: national food security and overall biosafety. These strategic objectives were originally set by Academician Dmitry Belyaev, who initiated the Chergin experimental farm. Now, in partnership with the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, we are recommitting to this vital work for our country.

– You mentioned that TSU already has significant major partners for the joint implementation of plans related to the experimental farm and the territory itself. Who are they?

– We have several major partners who are integral to the success of this ambitious project. One of our key partners is AFK Sistema PAO, the largest public investment company in Russia. We have established an agreement with them to create an RnD Center focused on biotechnology. This center’s primary objectives include the development and implementation of cutting-edge technologies for producing high-value raw materials, such as deer antlers.

Another major partner is Sberbank, with whom we have formed a joint group to align our development strategies. Sberbank is committed to significant investments aimed at building infrastructure for scientific tourism and creating a year-round educational cluster. This cluster will facilitate the training and retraining of not only its employees but also those of all our partners in the Altai project. The infrastructure developed will support a range of activities, including field practices for staff and students, as well as tourist attractions. This collaborative effort aims to establish a unique recreational zone to support the physical and moral well-being of corporate partners' employees.

Together with Sberbank and AFK Sistema, we are exploring other exciting ventures. For instance, we are considering an astronomical project, capitalizing on Altai's exceptional astroclimate. This project involves building an observatory and procuring state-of-the-art equipment, which would benefit scientific research, education, and tourism. Additionally, we are looking into the creation of a modern school for service, tourism, and hospitality, in collaboration with MGIMO University of the Russian Foreign Ministry and Gorno-Altaisk State University. This school would offer educational programs akin to those in Switzerland, combining academic study with practical on-site training.

In terms of production partnerships, we are collaborating with LLC Artlife and Tomsk-based company SAVA. With Artlife, we plan to produce dietary supplements using technologies and recipes developed at TSU, as well as engage in the collection and cultivation of medicinal herbs for both product development and cosmetics. SAVA is prepared to support the production of various deep-processing products, including those derived from berries, nuts, and mushrooms.

The scope of the Altai project is indeed monumental. The metaphor of the "Altai Noah’s Ark" feels quite fitting, reflecting the vast potential and significance of our endeavors.

In conclusion, I would like to emphasize once more that TSU has always been present in Altai, studying and describing its natural riches, and training personnel for the region. What is happening now marks a new stage in our presence and a new phase in forming a knowledge economy in this territory alongside our partners. I want to especially thank all TSU team members, whose tireless efforts are transforming the Altai project from a world of ideas into a realm of real deeds!

TSU Rector Eduard Galazhinskiy,

Member of the Council for Science and Education under the President of the Russian Federation,

Vice-President of the Russian Uni on of Rectors

Interview recorded and informational materials selected by Irina Kuzeleva-Sagan

For your information:

In the 1970s, Dmitriy Belyaev organized an expedition to Altai to sel ect a site for a proposed farm, with the primary aim of creating an insurance fund for wild mammals and rare livestock breeds. This initiative was crucial for supporting biodiversity and preserving the genotypes of endangered animal and bird species. The Cherginsky state farm was identified as the most promising location due to its diverse climate and vegetation zones and its ample grazing land — 80,000 hectares suitable for various animal and plant experiments.

Thanks to Belyaev's exceptional determination, the experimental farm with a protected regime was rapidly established. It gathered valuable breeds of cattle, including Highland, Jersey, and Galloway cattle, as well as French Aquitanians and Kalmyk, Yakut, and Gray Ukrainian breeds, which demonstrated unique resilience to extreme environmental factors. Notably, the farm also introduced the Kian breed, the largest domestic meat breed in the world, comparable in size to half an elephant. Additionally, Yakut and Altai horses, Kulundin fur sheep, and a farm for breeding marals and bisons (brought from the Prioksko-Terrasny Reserve) were included. The farm also housed rare and endangered bird species such as ulars and geese.

The farm’s territory was home to around 60 animal species, including large ones like moose and roe deer, as well as wild marals and Tochar deer in the foothills. Tasks included the domestication and taming of animals and birds to ensure their survival and commercial breeding. For instance, experiments were conducted with otters to achieve fur colors similar to mink without losing their valuable qualities. Plans were also made to introduce trout and whitefish into local water bodies to provide food for the otters. Efforts were made to domesticate various birds, including capercaille, black grouse, hazel grouse, mountain turkey, and wild hens, and to house endangered birds like the Altai ular, mountain goose, dryland goose, bearded vulture, osprey, and peregrine falcon within the farm's territory.

In parallel, the farm addressed grain production under the conditions of Mountain Altai. Agricultural practices saw significant changes with the introduction of valuable winter wheat varieties and a specialized crop rotation system. Despite the unfavorable summer of 1981, the farm harvested 40 quintals per hectare of wheat, with the potential to double its productivity. The establishment of a winter grain area in Siberia was envisioned as a foundation for local grain farming. Additionally, new forage production technologies were implemented to obtain two harvests per year, with crops such as spring rapeseed, clover, alfalfa, and sweet clover. The farm began producing notable outputs, including 27,000 quintals of milk, 8,500 quintals of meat, 500 quintals of wool, 5 quintals of goat down, and nearly 800 quintals of antlers. A settlement was built to accommodate and provide work for 200–250 research staff, including laboratories, residential houses, a school, a store, and facilities for everyday services.