This issue of the blog raises questions regarding the state of modern scientific knowledge and education in social studies and humanities, as well as their role in the life of society in the 21st century in the context of new socio-political realities.

- Professor Galazhinskiy, in the November issue you spoke of the clash of cultures and civilizations affecting the processes of education. You announced today's conversation topic as "the role of the social sciences and humanities in shaping the cultural identity of the young generation." What prompted you to expand on the topic?

– Since the publishing of the November issue, a lot of events have taken place, which explicitly or indirectly affect the issues of social studies and humanities. In addition, the reaction on social networks to the November issue was so ambiguous and sometimes beyond the normative public discourse that it became clear the topic on cultures, civilizations and values touched one of the most vulnerable and painful areas of public consciousness and confirmed its super-relevance. We are also now living in a period of another head-on collision of different cultures and civilizations: conservative vs. neoliberal, traditional vs. non-traditional, globalist vs. national, and Western vs. Eastern. Since people of various ages and social statuses participated in the network discussions, it probably makes sense to talk about the “sciences of culture”, focusing not only on the younger generation.

- Almost any conversation about social studies and humanities begins with a statement on their deep crisis. Will today's conversation be an exception?

- Unfortunately, no. This crisis declared itself, indeed, a very long time ago. And so far it is only growing, giving rise to more and more issues, one way or another connected with scientific knowledge in social studies and humanities. The initial cause of the crisis was the polarization of two cultures — natural sciences and humanities. It began to emerge during the Enlightenment, when the bright achievements of scientific and technological progress based on the laws of mechanics discovered by Newton, for some time, overshadowed the achievements of philosophers, poets and artists of the Renaissance, based on the ideals of Antiquity.

- It turns out that the dispute between "physicists" and "lyricists" arose earlier than the 1960s?

– Yes, it did. The dispute of the sixties is only one of the manifestations of a long tradition of a gap between the two scientific cultures, which existed not only in our country but abroad. Discussions about it has arisen at various times, for example, in British universities and even in the British Parliament. In the Soviet Union, if I remember correctly, the military engineer and cybernetic physicist Igor Poletaev and the poet Ilya Ehrenburg started to develop this topic. In Moscow in the 1960s, a whole series of public debates took place, in which many representatives of the engineering, scientific and creative intelligentsia participated on both sides. And this topic remained on the pages of the central newspapers for almost a quarter of a century. It is hard to imagine nowadays when no agenda stays in the media for more than three days. Poems, films and even essays of university applicants during the entrance exams have been devoted to the dispute between “physicists and lyricists”.

I must say that humanities scientists are already so accustomed to the crisis in their field of scientific activity that they consider it a way of life. Some are convinced knowledge in humanities cannot exist without a crisis at all, which is constantly described by the knowledge itself. In other words, crisis is an integral characteristic of this type of knowledge. This is explained as follows: because of their greater capacity for critical thinking, which is one of the main aims of the "social humanities", scholars in humanities reflect more frequently and more deeply on the general situation in their academic field than representatives of the natural or exact sciences do.

- Then maybe one needs to reflect, evaluate and engage in self-criticism a little less?

- Stepping on the throat of one’s own song, or rather, one’s own critical thinking, is unlikely to succeed. And if it works out, then this is no longer critical thinking. By and large, the growing crisis of social humanities knowledge in the 21st century is a global trend, observed not only by subjective feelings and assessments of its immediate bearers, but also by many objective factors and figures.

– But isn’t this global trend a natural course of events due to the uselessness of the social humanities for modern society and people, or, at least, for those who consciously chose a profession in engineering?

– I would like to note that technocrats pose the question exactly that way, as a result of which there is an intensive “erosion” of socio-humanities disciplines from the curricula of technical universities and majors. Their arguments, most often, come down to the fact that there is a massive and widespread dissatisfaction among tech students who have attended certain courses in humanities and consider them completely useless. For the most part, future engineers and mathematicians have no idea why they might need knowledge of specific historical dates and abstract philosophical and political theories in their professional performance. Moreover, there is Google that knows everything, as well as ChatGPT that is gaining power and exploding as we speak. But it is not techies who are to blame for this state of affairs, but the humanities themselves, who cannot interest students and convince them of the need. Understanding and awareness of this need by students depends not only on the professor’s enthusiasm and on the methodology of teaching, but also on the content of a particular course. And it, in turn, depends on the state of knowledge in social studies and humanities as a whole.

- It then appears that the crisis of knowledge and education in social studies and humanities is generally insurmountable, and that sooner rather than later, they will cease to exist as a socially demanded sphere of professional activity.

- Here is a paradoxical idea: this crisis can be overcome relatively easily. You just need to not participate in it. First, do not remove the humanities from schools and universities, despite all the recommendations. As an example, the two leading universities in Japan, Tokyo and Kyoto, did when they were offered to change the programs to eliminate time spent in vain on training humanities specialists and to remove the distraction from the natural and exact sciences for engineering students. Secondly, turn social studies and humanities towards the human being and everything that contains the “human” element in it. Thirdly, develop interdisciplinary connections between social studies and humanities with other areas of scientific knowledge, thereby proving its naturalness and inseparability from modern life, scientific and technological progress, and scientific knowledge as such. That is, it is necessary to turn the vector from the “gap” to the “dialogue” between the social studies and humanities, on the one hand, and the exact and natural sciences, on the other. Fourth, learn to convey this objective truth to all students, including future engineers, mathematicians, chemists, biologists, and so on.

Truth be told, to do that one needs to discover the ability to see this very social humanities component literally in all the achievements of the scientific and technological revolution and understand its value for the development of the creative potential in all inventors, no matter what industry their innovations belong to. To develop this ability in today’s engineering students, it is necessary to analyze with them as many cases from real-world experiences as possible. It would show the connection between the results of professional activity of a technical nature and this very social and humanities component.

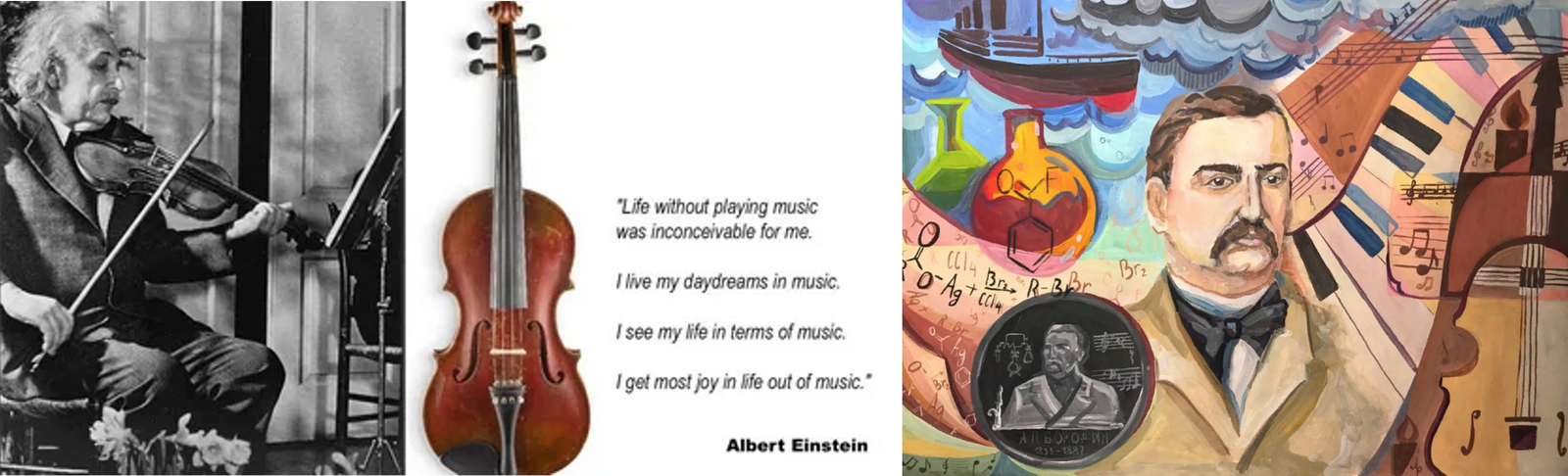

- Something like stories about how the theoretical physicist Einstein played the violin or the chemist Borodin composed operas?

- Why not? Although it must be admitted that for modern youth these are people of completely different eras, and therefore such stories are no longer very impressive. Here we need examples closer in time. I was convinced that it worked even when I was teaching a course in management psychology at our university. For live communication with students and development of their motivation for future work, I often invited managers who had achieved success in their professional careers to my classes. Today, it seems to me that relevant examples could encourage future IT specialists to treat the social sciences and humanities with great respect and develop an interest in them. Here are some examples that prove that the socio-humanities component is strong in every truly exciting achievement of scientific and technological progress. Despite the fact that Apple was initially perceived primarily as a technical company, its founder and CEO Steve Jobs always attracted many experts in humanities to cooperate, emphasizing their special role in what the company produced. Jobs, who was fond of calligraphy, tried to ensure that Apple products were distinguished not only by their super-functionality and the highest quality but also by their super aesthetics. At the same time, he proceeded from the fact that design was not how the product looked, but how it worked.

This approach is also recognized by our best domestic inventors and innovators. Once, the legendary Soviet aircraft designer Andrei Tupolev was shown a model of an aircraft. Assessing its appearance, he immediately and confidently said that it would never fly. The question “Why?” was followed by the answer: “Ugly planes do not fly!”.

Developing this topic, we can assume that the aesthetic taste of a person is his or her intuitive awareness of what corresponds and what does not correspond to the physical laws of the world. To determine this, a person with a developed aesthetic taste does not need to do any calculations. Thus, the aesthetic taste of future engineers, on which, among other things, socio-humanitarian disciplines are working within their professional training, is not even a soft, but a hard skill. That is, a mandatory skill that is part of the “core” of their profession.

– But as we all know, we cannot form such a skill only by the forces of one socio-humanities discipline, and even “by choice”.

- Undoubtedly! That is why the best domestic technical universities have always had a whole range of socio-humanities disciplines. Their corporate culture and the entire environment, including the interior of classrooms and the dress code, were designed to solve the task. So, for example, students of the first higher engineering school in Russia, on the basis of which the modern St. Petersburg Mining University was founded, mastered fencing, music, theatrical art, and learned to sing and dance. At present, the St. Petersburg Mining University is one of the few Russian “civilian” universities (if not the only one) where it is mandatory for all students — boys and girls—, as well as for professor, to wear a mining engineer’s uniform, very similar to the one that was worn by Russian mining engineers before the 1917 revolution. Needless to say, this creates a special upbeat and beautiful atmosphere and a more responsible attitude to learning and teaching. Few people today know that in the 19th century the Russian engineering school was recognized as the best in the world. It is clear that the reason for such success was an integrated approach to the training of engineers, including their aesthetic education. In general, psychologists have long understood that art and engineering have much in common in the cognitive evolution of a people, that is, the evolution of their consciousness, thinking, and perception.

To be continued