– Professor Galazhinskiy, when we started our conversation about intellectual sovereignty, you decided to dwell on three main points related to this issue. So far, we have discussed two issues: the awareness the academic community needs to pursue intellectual sovereignty and the need to reevaluate the “quantitative” attitude towards big science, when it is seen as the result of common efforts of many scientists. The third issue to be discussed is the ongoing search for a new ontology of the University, capable of ensuring the formation and maintenance of intellectual sovereignty as a synthesis of domestic great science, an effective system of education and culture based on Russian national codes.

– Indeed, today we are turning back to the topic of the modern University’s search for a new self, although we have talked about it on this blog more than once and in different contexts over the last nine years. But this topic will never exhaust itself, because self-reflection and self-description are natural properties of the University as a unique organizational structure that can exist for centuries. Thanks to historical university chronicles, statutes, codes, dissertations, monographs, papers, and current corporate social networks, we can find out why and how the University has changed and is changing. Probably, if the University had not been engaged in such constant critical self-analysis for further self-improvement, it would have outlived its usefulness long ago and ceased to be one of the main institutions of human society. Let us consider that this blog and, specifically, today’s “conversation about the complex” is a part of an endless general discourse about the University, which is in constant search for its most relevant models and ontological metaphorical images that describe them.

Metaphorizing the idea of the University is very important, since it is one of the methods of linguistic modeling. Each time this search is determined by new historical contexts. What contexts are we dealing with now? I will highlight two main ones. The first is the advent of the digital network society with all its intractable problems and super complex and constantly changing architecture. The second is the processes of deglobalization and political crises that have begun in the world, accompanied by the need for countries to acquire their national sovereignty, including technological and intellectual ones, which, in turn, makes reforming the spheres of science, education and culture inevitable. And Russian universities are fully immersed in both of these contexts.

– Before moving on to the present phase of the University’s self-reflection and its search for a new self, let’s focus on the main “reference points” in the evolution of the metaphorizing the idea of the University.

– One of the first prototypes of the University is considered to be the ancient Lyceum, the god Apollo’s sanctuary. Socrates and Aristotle wandered with their students in his gardens, discussing the structure of the world around them. It was already the 11th century, when the first university, Bologna, appeared in Europe. The contemporaries called it the Church of Reason, since it immediately demonstrated its ability to produce popular ways of describing the world and, thanks to this, occupy a special position in society along with the church. (In particular, there was a revival of Roman law at the University of Bologna, which was then taught in all European universities).

Then it was at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, when three outstanding historical figures — the English political economist Adam Smith, the French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte and the German philologist, philosopher and statesman Wilhelm von Humboldt — expressed different opinions about the real mission of the University, which became the ideological prototypes of three different modern models of the University.

Adam Smith believed, for example, that the professors’ work should be paid for exclusively fr om the pockets of students, and not from the state because this was the only way to determine the real demand for studying at a university and create an appropriate supply. Education is a special service that creates the abilities of people through the transfer of knowledge, which gives them the opportunity to receive an appropriate income in the future. Bonaparte, on the contrary, saw the University exclusively as a state entity that deals with the training for specific fields. At the same time, he categorically separated science from the University, considering it too abstract a phenomenon and incomprehensible from the point of financing. Wilhelm von Humboldt, as we now know, went the furthest. He created a University model that combined education with science and the idea of academic autonomy as the relative freedom of a higher education institution in vital issues of its functioning. Therefore, the first prototype of the university may be described as a “business corporation”; the second as a “state institution” with its principles of strict planning; the third as a “country of scientists and students'' and an independent institution that critically comprehends the picture of the world through scientific research and the transfer of knowledge to younger generations.

In 1930, the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset asked himself and society the question of why universities are needed in his famous lecture The Mission of the University. The answer he proposed was that the main goal of the University is to help people understand their time and themselves in this time. From this point of view, the Ortega y Gasset University appeared simultaneously in two forms. Firstly, as a Universe in which all knowledge and sciences were ordered around a culture that made a person, as a mammal, a person who “feeds on truths.” Secondly, as a place, wh ere people gathered to jointly search for the truth. The results of the Second World War led to the emergence of an ontological metaphor of the University as a social engineer or “mechanic” who, in many respects, needed to rebuild the European world destroyed by the war or “repair” what was still preserved in it. We see that in the 20th century the University begins to lose its former sovereignty, and in many cases, autonomy. Its mission is becoming more and more “utilitarian,” which is reflected in its new metaphorical images and in the technocratic language of self-description. At the same time, the University is increasingly being used by European states as one of the most effective instruments of social policy.

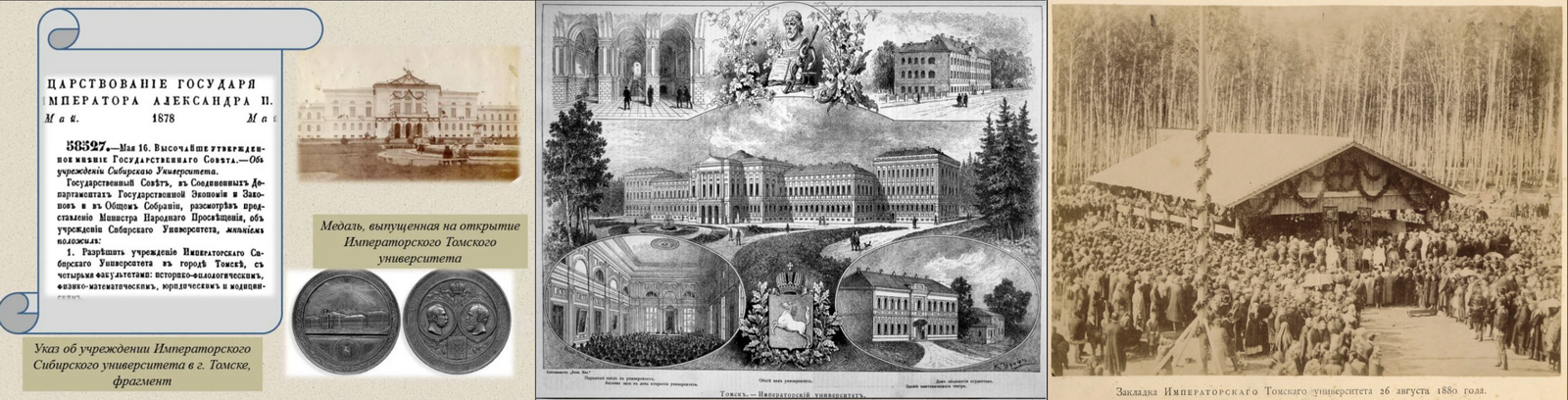

It must be said that the same thing happened in the USSR (the mechanisms of quota for admission and distribution after graduation), and even earlier, in the Russian Empire. After all, the Imperial Tomsk University was also conceived and implemented as a grandiose project, the purpose of which was to draw the vast territory of Siberia into the socio-cultural space of Russia and the development of its natural resources.

In the second half of the 20th century, Europe and the USA offered other approaches to understanding the role of the University with corresponding ontological metaphors: the university as a “business corporation” and a “political party”. In the latter case, the main mission of the University was proclaimed to be the production of political elites. Examples are Yale and Harvard universities. By the end of the 1990s, the philosophical and scientific discourse about the purpose of the University and its role in society intensified, which was associated with the emerging processes of economic globalization, universalization of cultures, computerization, networking and other technological trends. It did not weaken in the 2000s, when the largest countries faced a deep economic crisis again. All these trends and events had given rise to many pessimistic statements on the topic of “the death of the university.” But among them there were those who foreshadowed its subsequent revival. First of all, the famous lecture Making Sense of the University (1997) by Ronald Barnett, professor at the Institute of Education, University of London. I have already talked about it more than once, so I won’t go into too much detail now. I will emphasize only one of Barnett’s main ideas, which is especially close to me: the University gives rise to super-complexity and at the same time teaches us to live with it.

– Don’t your examples confirm that thoughts about the University, by and large, always concern only the elite?

- No, they do not. We can give examples that show that the broadest layers of society are able to understand the role of the University in their lives and build appropriate priorities even in the most difficult times. Among them is the history of the creation of the Imperial Tomsk University, supported not only by the local nobility and merchants, but also by ordinary townspeople. It is believed that the decision made by Alexander II and his government to choose a city beyond the Urals for the construction of the first university was influenced by the active position of the Tomsk public and their readiness to give money and make other donations for a good cause.

People at all times understood or intuitively realized that in order for their country, region or city to “live by its own mind,” this mind needs to be honed somewhere and that the best place for this is the University. Today, judging by individual statements and heated discussions on social networks, a huge number of Russian citizens, even those who are not members of the academic community, are also not indifferent to what the University will be like in the coming years and in the long term. It is clear that they are primarily concerned about the problems they face in their daily lives such as the digital inequality among young people and adults, the preparation of high school students for the Unified State Exam which distracts them fr om real learning, the disadvantages of the Unified State Exam as a social elevator. After all, not everyone can pay for the services of professional tutors. The result is inequality of access to good higher education. The new design of the University model must take into account existing problems.

But there is also an order from the state! I am referring to such urgent and medium-term tasks as ensuring economic and social stability in the country, educating young people and also their so-called high-quality employment, which Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke about at the recent St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. And, of course, there are tasks associated with the formation and maintenance of technological and intellectual sovereignty - the creation of great science, without which real innovation is impossible, and that of educating generations capable of maintaining traditional values and cultural identity. One way or another, such requests from our society and the state point precisely to the University 3.0 model, which is now being discussed in all forums and in almost all discussions concerning domestic higher education.

– Why is there such an interest in this model again? After all, the idea of University 3.0 itself arose quite some time ago. Moreover, many people are now talking about University 4.0.

– Indeed, it is believed that the origins of the University 3.0 model are two world-famous researchers: Burton Clark and Johan Wissema. The first published his book Creating Entrepreneurial Universities back in the late 1990s, the second published his book The Third Generation University at the end of the 2000s. Both books have been mentioned in my blog more than once over almost ten years when we discussed the target model of our university. Both authors consider the transformation of the traditional “Humboldtian” university inevitable and see its peculiarity in the focus on entrepreneurial activity. The difference between their concepts is that while Clark’s basis for the transformation of a traditional university is external conditions - the need to develop an innovative economy and the transfer of knowledge in technology, Vissema’s basis is internal conditions - the university’s struggle to source funding, the best professors and students.

Currently, the Russian higher education system consists mainly of two types of universities: 1.0 and 2.0. Model 3.0 is just beginning to make its way into life. Tomsk State University is one of the few Russian universities that have not only shown interest in these ideas, but have also been working in this direction for several years, developing the characteristics of University 3.0. This vector of development for TSU was confirmed back in 2017 by Johan Wissema himself, with whom we have been collaborating for the past few years.

As for the University 4.0 model, this is an uncommon phenomenon all over the world, not just in Russia. It seems that in the foreseeable future such a model, if reduced to a digital learning platform, even a very advanced one, cannot be scaled up enough to become the basis of national higher education systems. In my opinion, its functionality can only be considered as an addition to the basic 3.0 model. Otherwise, it will be higher education not for people, but for cyborgs. If it is understood more broadly and deeply, without diminishing the role of a living teacher in the learning process, then, most likely, this will truly be the next stage in the evolution of the University model with a focus on adaptive technologies, big data analysis, blockchain technologies and artificial intelligence.

– Why is it so difficult for University 3.0 to take root on Russian soil?

– There are many objective and subjective reasons for this, including sociocultural factors. In recent years, a number of scientific publications have appeared in which these reasons are analyzed in detail. Therefore, I will not dwell on this. Let me just remind you that delay has its advantages. In particular, the opportunity to study other people's experiences. We don’t have to learn only from our own mistakes! Quickly copying other people's cases, as a rule, does not lead to anything good. For example, one of the conclusions made by some followers of Vissema’s ideas from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (USA) was this: “No lectures, no classrooms, no specialization, no departments!” We have a different point of view on this matter. At the same time, we see that we can no longer delay. Realizing the need to transition the national higher education system to the University 3.0 model as the base model for a significant number of domestic universities in the near future, we believe that this model can be completed in one way or another, depending on the specifics and potential of each particular university. Synthesis of various models is also quite acceptable. Thus, at Stanford University (USA), the leader of all world rankings, signs of both Model 3.0 and Model 2.0 are clearly visible. That is, it is undoubtedly both an entrepreneurial and a research university. I am sure that this approach is also productive in relation to Tomsk State University. This is the only way to overcome the contradiction between the fundamental and the “redundant” on the one hand; practice-oriented and specialized on the other.

Today, the University 3.0 model is no longer something abstract for us, as it was, say, 10–15 years ago. The difference between its target function and the previous 2.0 model was very precisely formulated by the Minister of Higher Education and Science of the Russian Federation, Valery Falkov at one of the discussion panels of the 2023 St. Petersburg Economic Forum, as was TSU's place in the transformation of the national higher education system.

And this, by the way, is the answer to the question of why TSU became one of six Russian universities that entered into an experiment to develop new programs as part of the transformation of the national higher education system, the implementation of which begins in September 2023.

At the last St. Petersburg forum, a number of experts noted that the transition of leading Russian universities to the University 3.0 model is being carried out in conditions wh ere the main sectors of our industry rely primarily on domestic technology developers and manufacturers of high-tech products. Universities have a unique opportunity to use this situation for the purpose of their development: to create their own lines of development of key technologies and innovative products, bringing them to a level of readiness that allows them to transfer these technologies into production. In this way, they can respond to the industry’s request and solve a number of financial problems.

We know that our higher education system is underfunded. And over the past 20 years, this problem has not been solved due to the peculiarities of the domestic budgetary and financial system. Unfortunately, the funding standards for universities do not make teaching a desirable choice for the brightest and most talented young people. And those universities that can take advantage of the situation outlined above will be able to develop very quickly and successfully in the next 5, 10, 15 years. At the same time, they will be able to form an appropriate educational structure and become serious players in the market of new knowledge and technologies. Global scientific and technological universities, e.g. Stanford and MIT, became such precisely after the Second World War when they received a long and serious order for R&D, including defense. Due to this, they increased their resources, which later allowed them to collect talents from all over the world. They attracted a lot of Nobel laureates and creative youth. As a result, they themselves became “factories” of thought, new technologies, products and new people, the totality of which in each of these universities creates the same gross product as some individual countries. This is an important challenge for each of the leading universities to choose their own path.

– You have been working as the TSU rector for ten years and know its potential well. During this time, the university has repeatedly confirmed its status as a leading national research university or University 2.0, which in recent years has made confident steps towards the University 3.0 model. This raises the question: what needs to be the first focal point for TSU to finally turn into University 3.0?

– The development of ecosystem management skills among both employees and students to the extent that would allow TSU and the entire Big University of Tomsk to become the center of the regional ecosystem, focusing on the appropriate tools and resources for cluster and industry development. That means that educational and even research competencies alone are no longer enough. Technological and business competencies coupled with an entrepreneurial culture are needed. Only then does the University become a center of change, an agent of development of the region, industry, and country.

To be continued